Week of May 1—He Said, She Said—Dialogue in Picture Books

Wednesday, May 4—Dialogue vs. Voice

I’m about to wade into some murky water. Since I live in Florida, I know the dangers of murky water . . .

. . . despite the danger, I’m wading in!

When I’m with other writers (and writing teachers), there’s often a lot of confusion about the difference between voice and dialogue. When we throw character development into the conversation, the confusion grows and grows and grows. Let me make two statements to begin to clear up the issue.

Voice belongs to the writer.

Dialogue belongs to the characters.

You could hand me two books—one by Margie Palatini and one by Lisa Wheeler—and I could tell them apart just by the author’s voice. Palatini’s humor, word play, and puns are distinctively her. Wheeler’s pacing, word choice, and rhyming patterns are her signature. Voice is the author’s personality, his/her heart. We need to spend time talking about voice, but we’ll save that for another day (or days).

Now if you were to read only the dialogue from books to me, it would be more difficult for me to distinguish the author. That’s because character dialogue fluctuates to match the personality of the character and two authors might have similar characters in their books with similar dialogue. Yesterday we looked at Tammi Sauer’s Elvis Poultry character from Chicken Dance. Chances are, almost any author is going to write a similar character’s dialogue in a similar way—

“Ah-one for the money. Ah-two for the show. Ah-three to get ready . . . Thank you. Thank you very much.”

While voice shows the author’s personality, dialogue shows a character’s personality. Each character’s personality needs to be as distinctive as a fingerprint, so the dialogue of that character must be distinctive. Take a look at some of these Lisa Wheeler characters to see what I mean . . .

Annie Halfpint hollered,

“Now halt! You mean ol’ cuss!

Back to the top! Hey! I said STOP!

You makin’ fun of us?”

From: Avalanche Annie by Leslie Wheeler and Kurt Cyrus

Mary, Mary quite contrary,

she’s a walking dictionary.

“I think you mean encyclopedia.”

Mary’s such a know-it-all

even though she’s three feet tall.

“I’m actually three-feet-two!”

Always interrupting folks

with her comments and her jokes.

“Why didn’t the chicken cross the road?”

Correcting people when they speak.

Injecting humor, old and weak.

“Because she was chicken. Get it? Chicken!”

From: “The Interrupter,” Spinster Goose: Twisted Rhymes for Naughty Children by Lisa Wheeler and Sophie Blackall

Can you pick up the differences in characters through the dialogue? Even small changes in the text of dialogue can show differences in characters. Take a look at another example from Lisa (and also note the role of the dialogue tags in character development).

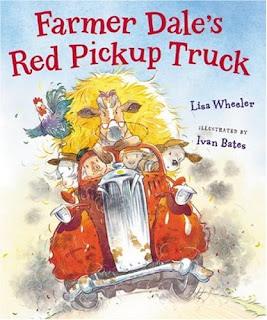

Farmer Dale’s red pickup truck

slowly rattled on.

A goat with an accordion

stood grazing on the lawn.

“Can I squeeze in?” asked Nanny Goat.

“My pleasure,” Farmer said.

“My pleasure,” Farmer said.

“Ba-a-a-d idea,” said Woolly Sheep.

“The engine’s almost dead.”

“No room!” lamented Roly Pig.

“We’re overcrowded now!”

“We’ll make some room,” said Farmer Dale.

“Mooove over!” bossed the cow.

From: Farmer Dale’s Red Pickup Truck by Lisa Wheeler and Ivan Bates

Dialogue allows us to give voice to our characters, to show their personalities, and to give them life. Did I make the murky water more muddy? Or is that crystal clear?

It’s Your Turn!

1. How is the dialogue of your characters showing their personalities? Can a reader distinguish between your characters through the dialogue of the characters? This would be a good time to stop and polish up that dialogue!

No comments:

Post a Comment